Disclaimer: This information presented here is to guide general public and provides an overview of the legislation in Australia. This should not be relied upon as a legal statement. Please seek legal advice regarding your personal circumstances.

The Commonwealth Definition

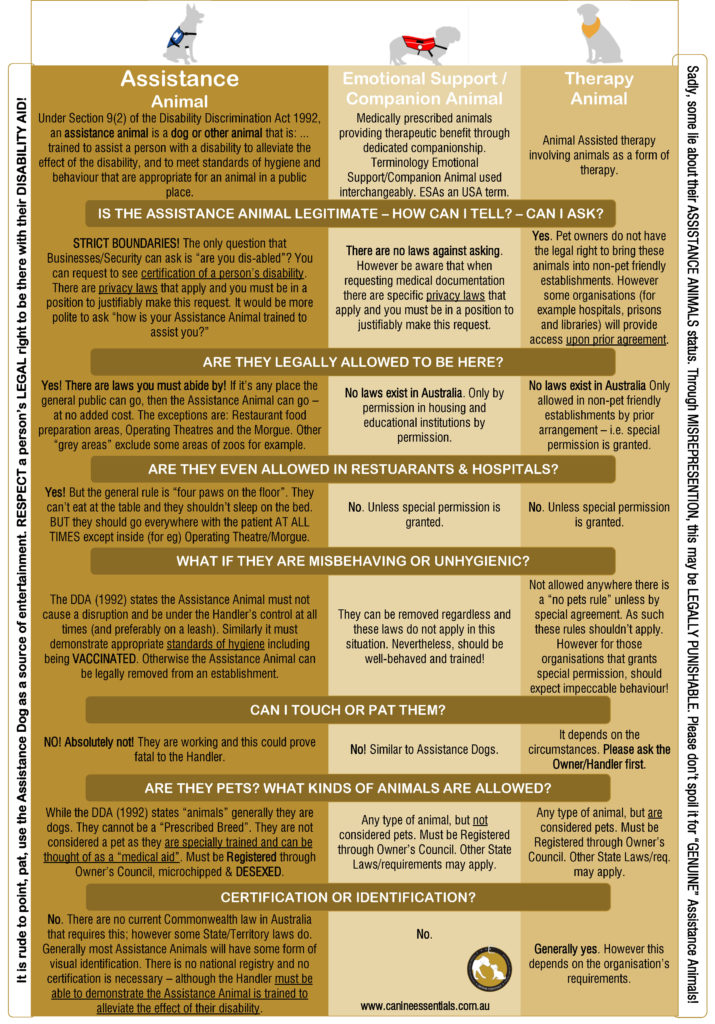

Assistance Dogs in Australia and members who utilise them are protected under the Federal (Commonwealth) Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA, 1992). An Assistance Dog is defined under this act as:

9 (2) For the purposes of this Act, an assistance animal is a dog or other animal:

– accredited under a law of a State or Territory that provides for the accreditation of animals trained to assist a persons with a disability to alleviate the effect of the disability; or

– accredited by an animal training organisation prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this paragraph; or

trained: to assist a person with a disability to alleviate the effect of the disability; and to meet standards of hygiene and behaviour that are appropriate for an animal in a public place.

According to the Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992, there is no distinction made between a Guide Dog, Hearing Dog or Service Dog – they are all considered to be Assistance Dogs. As such, from this point forward, the terminology “Assistance Dog” will be used instead of distinguishing between the different types of Assistance Dogs. The Human Rights Commission oversees discriminatory matters which includes discrimination Assistance Dogs and their Handlers may encounter while out in public.

For the purposes of educating the public to reduce discriminatory acts, Assistance Dogs:

“play a crucial role in enabling persons with disabilities to alleviate the negative impact of their disability. Guide dogs assist people who cannot see to navigate safely and alert people with hearing problems to noises such as fire alarms, telephones and the like. Assistance dogs assist people with a range of disabilities to avoid seizures, manage cognitive diseases and perform various other crucial services. There is occasionally a tension between persons with disabilities, who often require their [Assistance Dogs] to enable them to exercise their human rights, and some members of the public who hold prejudices against the presence of [Assistance Dogs]. Australian antidiscrimination laws empower persons with disabilities to be accompanied by their assistance dogs in most circumstances.” (Harpur 2010, p.49)

Queensland

The Guide, Hearing and Assistance Dogs Act 2009

The Queensland Guide, Hearing and Assistance Dogs Act is the only State Act in Australia that specifically mentions that specifically mentions Assistance Dogs and offers more transparency. This law is more restrictive than the Federal Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act (1992) in that it :

– Restricts assistance dogs access to ambulances.

– Restricts access to food preparation areas. This means kitchens, it doesn’t apply to the public spaces of restaurants and cafes.

– Authorises only approved organisations and individuals to certify assistance dogs.

– For long distance rail travel Queensland Rail accepts assistance dogs under the Commonwealth Act.

Public Access

Rights of Assistance Dogs as described by the Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992

Public Access means under the Federal (Commonwealth) Act, which, we now know supercedes any and all Australian state legislation, handler(s) and their dog (provided they meet the required training standards stipulated under the Act) have access rights to public places. These include restaurants and shops, public passenger vehicles (such as trains or taxis used to transport members of the public), healthcare facilities (with the exception of where infection control becomes a source of concern) and places of accommodation (such as hotels and campgrounds). It is unlawful under this Act to discriminate by refusing entry or access to a public place because a person relies on a guide, hearing or assistance dog. Assistance Dogs must accompany their handler at all times. They are not to be requested to be removed from their handler and it is deemed illegal to make such a request. The Human Rights Commission urges consumers who faces such discrimination to make a complaint and these will be dealt with accordingly. Strict fines do apply and businesses should be aware of their legal obligations.

Access to Healthcare Facilities

Access to facilities such as general practice surgeries or psychiatric services remain a source of contention and are one of the major organisational areas that seem to require educative measures to ensure that the community member who uses an Assistance Dog are protected. Strict fines do apply and again, businesses should be aware of their legal obligations.

According to the previous section, refusal of entry, or removal of the Assistance Dog from the community member constitutes a deviation from Federal Law. If one were to use a more common example, it would be unthinkable to ask that a community member who is blind have their Guide Dog removed from them during a session with a doctor, psychiatrist or psychologist. The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 makes no distinction between Guide Dogs or Psychiatric Service Dogs. So in this way, asking the Assistance Dog to be removed from the Handler is akin to asking a Guide Dog to be removed from the handler. This is clearly unacceptable and is in breach of the Act.

Interestingly, in the case of psychiatric services contrary to contemporary belief, animals have been used in mental health care as a successful treatment modality since the 18th Century (Shubert 2012). Importantly, given:

“the important role service animals play, a better understanding of the working animal-human bond would be instructive. (Peacock, Chur‐Hansen & Winefield 2012, p.301)

Issues of Regulations | Policies | Laws

Quoting directly from the Human Rights Commission:

The Australian Human Rights Commission recognises the work of the Victorian Disability Discrimination Legal Service (DDLS) in formally expressing to the Commission, its views on the current confusion around assistance animal legislation and policy in Australia.

The submission from the DDLS (accessible here) highlights apparent inconsistencies in laws and policies across the States and Territories, and between the States and Territories and the Commonwealth, which mean that people who use assistance animals face discrimination, uncertainty and a range of associated challenges to accessing the community…

Variation among states and territories regarding accreditation and regulation of assistance animals will continue to present a range of issues for people with disability who use assistance animals to access the community. Examples of the situation in each jurisdiction is set out below.

- Victoria – an Assistance Animal Pass is required and issued by Public Transport Victoria permitting assistance animals to travel on public transport. The pass is valid for 3 years.

- Western Australia – The Public Transport Authority doesn’t require permits for assistance animals to travel on public transport. There is local government legislation providing for animals to have an ID card and a dog coat/harness.

- Queensland – A Handler’s Identity Card is valid for 5 years allowing travel on public transport. Also, Translink (South East Queensland Transport Authority) issues an Animal Pass provided the dog meets certain standards of behaviour in public.

- South Australia – The Dog and Cat Management Board issues a Disability Dog Pass that is valid indefinitely.

- New South Wales – An Assistance Animal Permit is required for access to public transport, however Guide dogs and Hearing dogs do not require a permit. The permit must be renewed annually.

- Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory and Tasmania – no system of accreditation exists and no specific passes issued.

(Human Rights Commission 2017).

Liability of Damage

According to the leaders in Assistance Dog Standards, Assistance Dogs International has designed a “Model Law” that they encourage federal and state bodies to adopt. In this, they consider what should happen if the Assistance Dog should cause damage:

– The owner of an assistance dog is solely liable for any damage to persons, premises, or facilities including places of public accommodation, public conveyances or transportation services, common carrier of passengers, places of housing accommodations, and places of employment caused by that assistance dog.

– An “Individual with a disability”, including but not limited to, the blind, visually impaired, deaf, hard of hearing, or otherwise disabled who uses an assistance dog shall keep the dog properly harnessed or Leashed, and a person who is injured by the dog because of an “Individual with a disability”, including but not limited to, the blind, visually impaired, deaf, hard of hearing, or otherwise disabled failure to properly harness or leash the dog is entitled to maintain a cause of action for damages in a court of competent jurisdiction under the same laws applicable to other causes brought for the redress of injuries caused by animals.

The Difference between an Assistance Dog and a Therapy Dog

Assistance Dogs provide assistance to individuals with disabilities (mobility, sight, hearing, and other physical and/or psychiatric issues). They must pass a strict Public Access Test which is assessed by a qualified Canine Behaviourist. They are placed with the disabled individual or, in some cases, are trained by the disabled owner with the assistance of a qualified certified professional dog trainer. In this case the owner trained dog must still pass a strict Public Standards Assessment which is assessed by a qualified Canine Behaviourist. Assistance Dogs have public access rights and are now protected by the Disability Discrimination Act 1992.

A Therapy Dog provide visitation to hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities. They do not have public access rights and provide therapeutic interactions in facilities. Basic “good manners” skills should be evidents such as sitting, dropping, heeling and coming when called. The dog should also meet the minimum standards of an Assistance Dog when out in the public arena and this would mean they should be calm and maintain appropriate social behaviour in a variety of envionments. The dog should also be taught skills in order to be able to interact with people that have a variety of developmental/physical disabilities.

The information that is presented here has been accessed through freely available public documents and collated here for information purposes only. This is not a government fact sheet nor does it represent the opinions of Canine Essentials Pty. Ltd. Please seek information from authorities as referenced here before you draw your own conclusions.

References

Burris, S 2006, ‘Stigma and the law’, Lancet, vol. 367, no. 9509, pp. 529-530.

Disability Discrimination Act 1992, (Commonwealth of Australia).

Green, SE 2007, ‘Components of perceived stigma and perceptions of well-being among university students with and without disability experience’, Health Sociology Review, vol. 16, no. 3-4, pp. 328-340.

Harpur, P 2010, ‘Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Australian Anti-Discrimination Laws: What Happened to the Legal Protections for People Using Guide or Assistance Dogs’, University of Tasmania Law Review, vol. 29, pp. 49-79.

Human Rights Commission Assistance Animals and the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), Human Rights Commission, <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/disability-rights/projects/assistance-animals-and-disability-discrimination-act-1992-cth>.

Link, BG & Phelan, JC 2006, ‘Stigma and its public health implications’, Lancet, vol. 367, no. 9509, pp. 528-528.

Peacock, J, Chur‐Hansen, A & Winefield, H 2012, ‘Mental health implications of human attachment to companion animals’, Journal of Clinical Psychology, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 292-303.

Shubert, J 2012, ‘Dogs and human health/mental health: From the pleasure of their company to the benefits of their assistance’, US Army Medical Department Journal, pp. 21-30.

Western Australia Health 2015, WA Health Disability Access and Inclusion Policy, viewed 28 Nov 2016, <http://www.health.wa.gov.au/circularsnew/circular.cfm?Circ_ID=13191>.